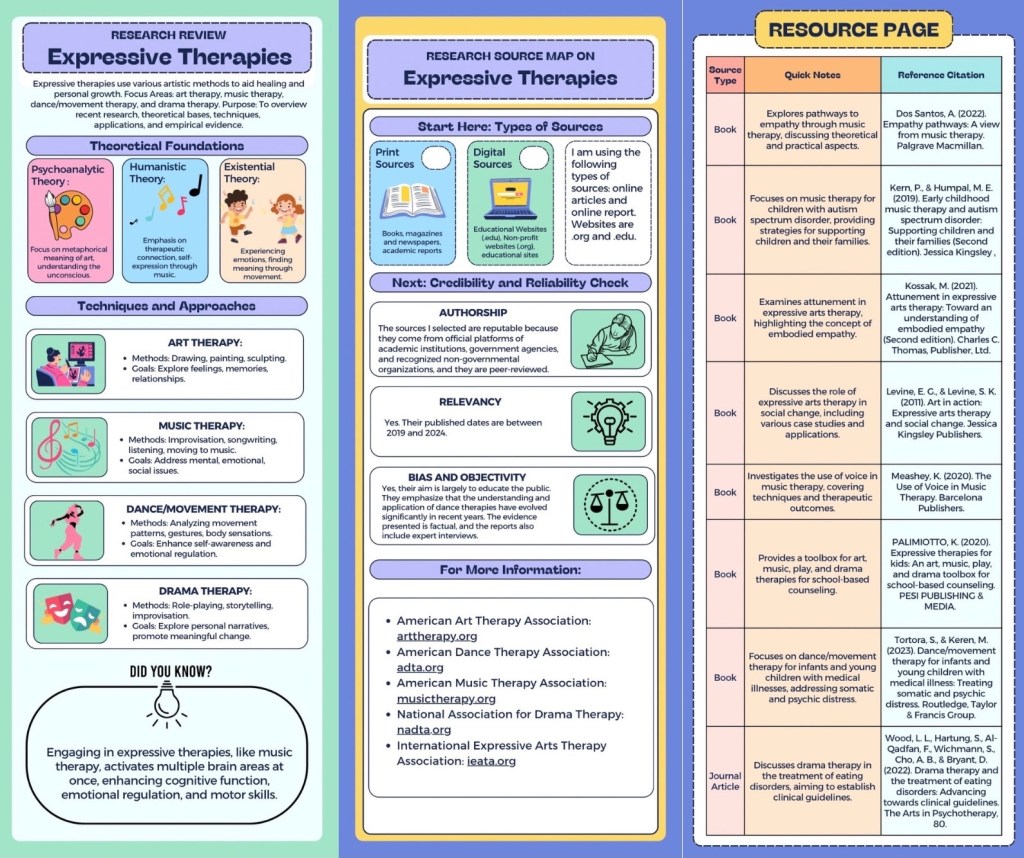

Have you heard of expressive therapies? You might be more familiar with terms like dance therapy or art therapy. This article provides an overview of the latest research on expressive therapies, exploring their theoretical foundations, techniques, applications, and the evidence supporting their effectiveness in treating mental health issues.

Expressive therapies

encompass a range of creative approaches, including art therapy, music therapy,

dance/movement therapy, drama therapy, and emerging methods that use the expressive arts to

foster healing and personal growth. I like to describe it as a way to express emotions that are

often difficult to put into words. Although expressive therapies are less widely known, they offer

numerous benefits and have substantial evidence demonstrating their effectiveness.

Theoretical Foundations

Speaking of its effectiveness, expressive therapies are grounded in various psychological theories, such as psychoanalytic, humanistic, existential, and behavioral approaches. For example, art therapy draws on psychoanalytic theories, emphasizing the symbolic meaning of art as a way to access the unconscious mind. By illustrating one’s emotions, nonverbal behaviors can be observed, and artwork can be interpreted to reveal deeper emotional states related to mental health. Humanistic theories are often applied in music therapy, focusing on the therapeutic relationship and the innate ability to express oneself through music. This mind-body connection helps individuals understand the harmony between their emotions and physical sensations. Existential theories play a key role in dance and movement therapy, emphasizing how emotions are experienced through the body and how movement can help individuals explore meaning and purpose in their lives. Drama therapy, on the other hand, is rooted in both existential and behavioral principles. It uses role-playing, storytelling, and improvisation to help individuals explore their emotions, gain insight into their life situations, and rehearse new ways of behaving. By acting out different roles or scenarios, clients can confront unresolved conflicts, develop emotional resilience, and gain a greater understanding of themselves.

Techniques and Approaches

Each type of expressive therapy utilizes specific techniques and methods tailored to meet the unique needs of the client. In art therapy, drawing, painting, sculpting, and other visual forms of expression help individuals process their feelings, memories, and relationships. Music therapy addresses mental, emotional, and social challenges through activities like improvisation, songwriting, listening, and movement to music. Dance/movement therapy fosters self-awareness and emotional regulation by encouraging individuals to explore their movement patterns, gestures, and bodily sensations. Drama therapy, on the other hand, employs techniques such as role-playing, storytelling, and improvisation to help individuals explore personal narratives and enact meaningful changes in their lives.

Applications in Mental Health Treatment & Empirical Evidence

Expressive therapies have been applied across diverse populations and professional settings, including individuals with mental illnesses, trauma survivors, children with developmental delays, older adults with dementia, and those grieving or experiencing loss. Research indicates that expressive therapies can benefit individuals with anxiety, depression, PTSD, and other mental health conditions by enhancing coping skills, boosting self-esteem, and strengthening interpersonal relationships.

Expressive treatments, like dance and dance/movement therapy (DMT), are getting more and more attention for their possible health benefits. Lopez-Nieves and Jakobsche (2022) did a review of the biomolecular effects of dance movements and DMT on different biomolecules in the body. They put together both clinical and experimental studies to show how dance can change hormones and small-molecule metabolites. The results show that dance practices might have an effect on body and mind, causing changes in biomarkers like nitric oxide, serotonin, estrogen hormones, and cholesterol levels. The real-world proof shows that including dance in wellness activities might be good for your health and gives us a better understanding of how it works as a therapy.

In addition, Lauffenburger (2020) looked into what makes DMT/psychotherapy (DMT/PT) different from other types of therapy. Lauffenburger used Koch’s framework for figuring out how well creative arts treatments work to come up with ten unique things about DMT/PT. Some of these traits are dynamic, creative interconnectedness mixed with ideas from psychoanalysis, psychology, and specific movement frameworks. By helping people understand these things better, dance movement therapists and psychotherapists can promote the uniqueness of their job in an ethical way. This empirical investigation shows how complex DMT/PT is and how it has the ability to bring about deep therapeutic changes.

Together, these real-world studies add to the growing body of proof that dance and DMT can help with therapy. Randomized controlled trials and longitudinal studies, among other types of study, are needed to help us better understand how these interventions work and how well they improve mental health.

Expressive therapies are a creative and all-around way to treat mental health problems. They combine creative expression with psychological ideas to help people heal and find themselves. As the field grows, more study and clinical practice will help us learn more about expressive therapies and how they might be used with a wide range of people.

References

Lopez-Nieves, I., & Jakobsche, C. E. (2022). Biomolecular Effects of Dance and Dance/Movement Therapy: A Review. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 44(2), 241–263.

Lauffenburger, S. K. (2020). ‘Something More’: The Unique Features of Dance Movement Therapy/Psychotherapy. American Journal of Dance Therapy : Publication of the American Dance Therapy Association, 42(1), 16–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-020-09321-y